In emergency medicine, the patient care report (PCR) narrative is more than just a task. It’s the cornerstone of patient safety, legal defense, and clinical continuity. A well-written narrative paints a clear, chronological picture of the call, allowing another provider to understand the situation in seconds, ensuring seamless handoffs and accurate billing. But crafting these critical reports under pressure, often after a chaotic call, is a skill that requires both practice and precision.

This guide moves beyond generic templates to provide a detailed breakdown of effective documentation. We will analyze eight distinct patient care report narrative examples, covering common and critical scenarios you encounter in the field. From chest pain and stroke alerts to trauma and behavioral emergencies, each example is dissected to reveal the underlying strategy.

You will learn not just what to write, but why it matters. We’ll provide specific, actionable takeaways and replicable methods for each scenario. Our goal is to equip you with the tools to document with confidence and accuracy, ensuring your reports are as effective and professional as your clinical care. Let’s dive into the examples that transform chaotic events into clear, concise, and legally sound records.

1. Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) Documentation

Documenting a potential Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) case is one of the most high-stakes tasks in emergency medicine. A detailed and precise patient care report narrative is crucial not only for continuity of care but also for legal and quality assurance purposes. This type of report must paint a clear picture of the patient’s presentation, the provider’s assessment, and the time-sensitive interventions performed.

This narrative serves as the definitive record of the event, guiding subsequent treatment decisions at the receiving facility. As outlined by organizations like the American Heart Association (AHA), a strong narrative captures objective findings methodically, from the initial complaint to the final handover.

Example Narrative: Suspected STEMI

“Unit 12 dispatched to a 62-year-old male reporting sudden onset of substernal chest pain. Patient describes the pain as a 9/10 ‘crushing’ pressure radiating to the left arm and jaw, which began 30 minutes prior while resting. Associated symptoms include diaphoresis, nausea, and shortness of breath. Initial vitals: BP 160/94, HR 105, RR 22, SpO2 93% on room air. 12-lead EKG shows ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, consistent with an inferior wall STEMI. Cardiac monitor initiated, showing Sinus Tachycardia. Oxygen applied at 2 LPM via nasal cannula, SpO2 improved to 96%. Aspirin 324 mg PO and Nitroglycerin 0.4 mg SL administered with partial relief of pain to 7/10. STEMI alert activated at ‘City Heart Center’ and ETA given as 15 minutes. Patient transported emergent, with continuous monitoring en route.”

Strategic Analysis

- Objective Description: The narrative avoids assumptions. Instead of “patient is having a heart attack,” it states “EKG shows ST-segment elevation… consistent with an inferior wall STEMI.” This focuses on factual findings.

- Chronological Flow: The report follows a clear timeline from dispatch to transport, detailing the onset of symptoms, initial assessment, interventions, and response to treatment. This logical progression is vital for understanding the case.

- Time-Sensitive Data: Critical time markers, like symptom onset and facility notification (“STEMI alert activated”), are explicitly included. These are essential for metrics like “door-to-balloon” time.

Actionable Takeaways

- Quantify Everything: Use pain scales (1-10), list vital sign numbers, and specify drug dosages. This removes ambiguity.

- Document Systematically: Describe EKG findings in a structured way (rate, rhythm, specific ST/T wave changes). This creates a replicable and professional report.

- Justify Your Destination: When bypassing a closer hospital for a specialty center (like a cardiac cath lab), always document the rationale. This is a key component of medical decision-making.

2. Stroke Alert/Neurological Emergency Documentation

Time is brain, and nowhere is that more evident than in the documentation for a potential stroke. A meticulously crafted patient care report narrative for a neurological emergency is the first and most critical link in the chain of survival. It provides the receiving stroke center with the precise information needed to make rapid, life-altering treatment decisions, such as administering thrombolytics.

This type of narrative must be clear, concise, and focused on time-critical data points. As emphasized by the American Stroke Association, the prehospital report sets the stage for in-hospital care, directly influencing patient outcomes by ensuring rapid and appropriate intervention.

Example Narrative: Acute Ischemic Stroke

“Unit 34 dispatched to a 71-year-old female for a possible stroke. On arrival, patient is found seated in a chair, alert but confused. Husband states symptoms began abruptly 45 minutes prior with ‘slurred speech and right-sided weakness.’ Last known normal (LKN) was 14:15 today. Assessment reveals positive Cincinnati Stroke Scale: left facial droop and right arm drift are present, speech is slurred. GCS 14 (E4, V4, M6). Vitals: BP 188/102, HR 88, RR 18, SpO2 97% on RA. Blood glucose is 115 mg/dL. Patient has a history of A-Fib and is prescribed Eliquis. Stroke Alert activated for ‘Metro Stroke Center.’ Transport initiated immediately. Patient remains stable en route, continuous monitoring maintained.”

Strategic Analysis

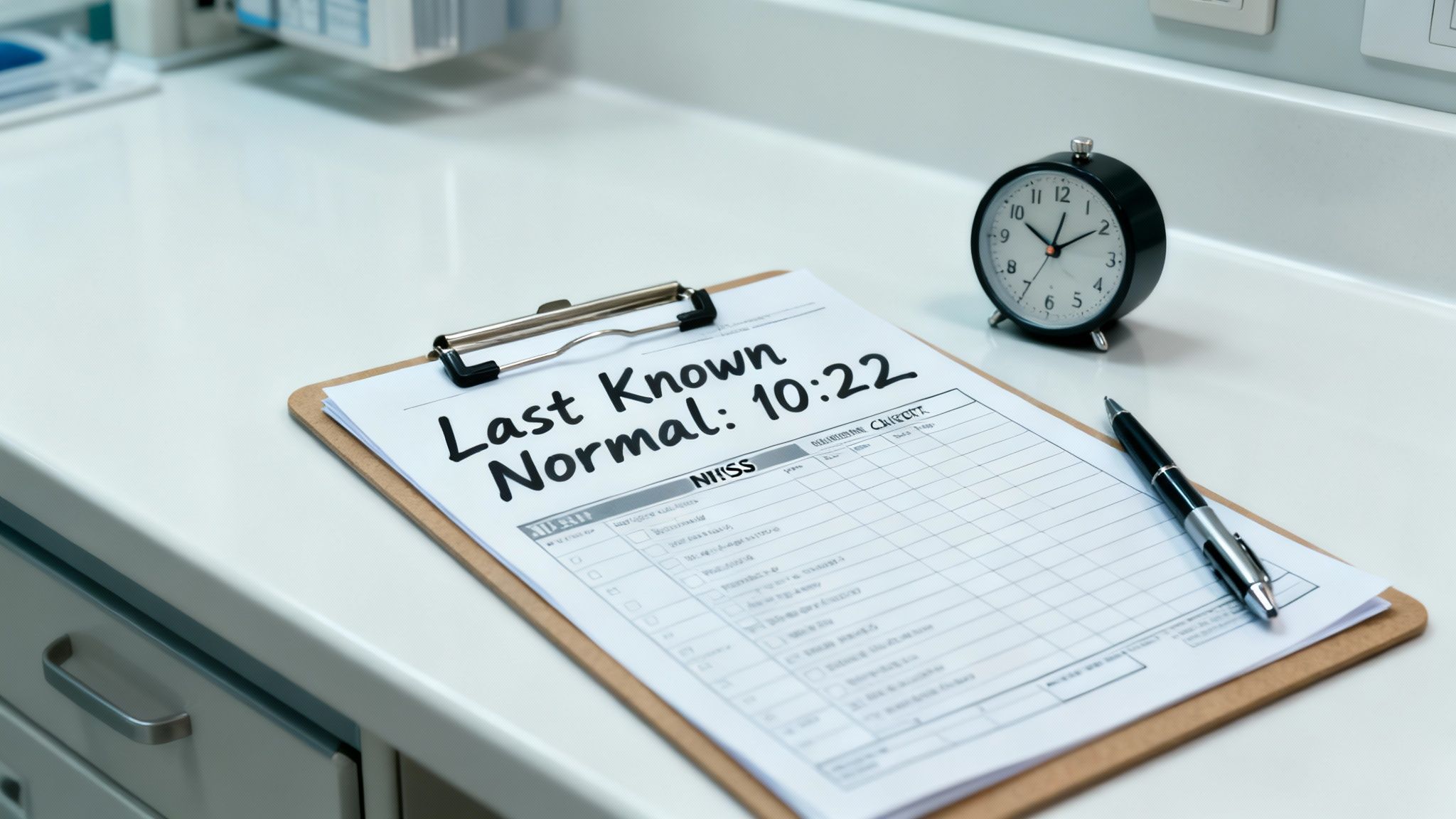

- Time-Critical Details: The narrative immediately establishes the “Last Known Normal” (LKN) time. This is the single most important piece of information for determining eligibility for time-sensitive treatments like tPA.

- Validated Scale Usage: The report explicitly documents the findings of a standardized tool (Cincinnati Stroke Scale). This provides objective, repeatable evidence of a neurological deficit rather than a vague description like “seems weak.” For effective neurological emergency documentation, a clear understanding of cognitive assessment principles is crucial, as these findings are central to a comprehensive patient care report.

- Exclusionary Data: Key information that could rule out other causes or complicate treatment, such as the blood glucose level and history of anticoagulant use (Eliquis), is clearly stated.

Actionable Takeaways

- Prioritize “Last Known Normal”: Always document the LKN time with precision. If the onset was unwitnessed, state that clearly (e.g., “patient awoke with symptoms”).

- Document a Full Neuro Exam: Beyond the Cincinnati scale, note specifics like grip strength, gait (if possible), and any sensory deficits. This creates a detailed baseline.

- State the Alert Clearly: Document the exact facility you alerted and why (e.g., “transporting to Comprehensive Stroke Center due to large vessel occlusion indicators”). This justifies your transport decision and is a key component of these patient care report narrative examples.

3. Trauma/Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) Documentation

Documenting a trauma case, especially from a motor vehicle accident (MVA), requires capturing a high volume of critical information in a short amount of time. The patient care report narrative must clearly articulate the mechanism of injury (MOI), the primary and secondary assessments, and all life-saving interventions. This detailed account is vital for the trauma team at the receiving facility to anticipate injuries and mobilize resources effectively.

A strong trauma narrative follows a systematic progression, from scene size-up to handover. As emphasized by trauma organizations like the American College of Surgeons, the report must paint a vivid picture of the scene and the patient’s condition, justifying transport decisions and treatments. These types of patient care report narrative examples are essential for training and quality improvement.

Example Narrative: High-Speed MVA

“Unit 34 dispatched to a high-speed, single-vehicle MVA with rollover. On arrival, find a 28-year-old male, restrained driver, self-extricated prior to our arrival. Heavy front-end damage to the vehicle with ~2 feet of intrusion. Patient found ambulatory at the scene, complaining of severe abdominal and left leg pain. Primary survey reveals patent airway, clear bilateral breath sounds, and rapid, thready radial pulse. Initial vitals: BP 90/50, HR 135, RR 28, SpO2 95% on RA. Head-to-toe reveals abdominal rigidity and guarding, and a deformed, edematous left femur. C-collar applied, patient secured to a long spine board. Two large-bore IVs established with 1L normal saline initiated wide open. Left femur splinted. Notified ‘Metro Trauma Center’ of a ‘Trauma Alert,’ ETA 10 minutes. Patient’s GCS is 15. Pain managed with 50 mcg Fentanyl IV. Continuous monitoring en route.”

Strategic Analysis

- Mechanism of Injury (MOI): The narrative details the “heavy front-end damage” and “2 feet of intrusion.” This information gives the trauma team crucial context to anticipate specific injuries like aortic dissection or abdominal organ damage.

- Systematic Assessment: The report logically moves from the primary survey (airway, breathing, circulation) to a detailed head-to-toe assessment, identifying life-threatening conditions like abdominal rigidity and a potential femur fracture.

- Justified Interventions: Each action is clearly linked to an assessment finding. Hypotension and tachycardia justify the aggressive fluid resuscitation, and the deformed femur justifies splinting.

Actionable Takeaways

- Paint the Scene: Describe the vehicle’s damage, patient’s position (e.g., ejected, entrapped), and use of safety devices. This MOI is as important as the patient’s vital signs.

- Document a Thorough Head-to-Toe: Systematically list findings for each body region, even if they are normal (e.g., “head is atraumatic”). This proves a comprehensive assessment was completed.

- Record All Trauma Data: Include the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, time of tourniquet application, or details of spinal motion restriction. This data is critical for triage and ongoing care.

4. Pediatric Respiratory Distress/Asthma Exacerbation Documentation

Documenting pediatric respiratory distress requires a unique focus on age-specific assessments and interventions. Unlike adults, children can decompensate rapidly, making a precise and detailed patient care report narrative essential for ensuring continuity of care and justifying treatment decisions. This report must clearly convey the child’s work of breathing, response to weight-based medications, and overall clinical trajectory.

A well-crafted narrative serves as a critical communication tool between prehospital providers and the receiving emergency department. As emphasized in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) guidelines, strong documentation captures objective findings methodically, from the initial assessment of respiratory effort to the post-intervention reassessment, painting a clear picture for the next clinical team.

Example Narrative: Pediatric Asthma Exacerbation

“Unit dispatched to a 6-year-old female with a known history of asthma in acute respiratory distress. Per parent, patient has had a cough for two days and began wheezing 2 hours ago with increased work of breathing. Patient is alert but anxious, speaking in 3-4 word sentences. Obvious subcostal and intercostal retractions noted with diffuse expiratory wheezing bilaterally. Initial vitals: HR 140, RR 36, SpO2 91% on room air. Weight per parent is 20 kg. Administered continuous Albuterol/Ipratropium nebulizer treatment. Following treatment, work of breathing is mildly improved with decreased retractions, and SpO2 increased to 95%. Patient remains tachycardic and tachypneic. Transported emergent to ‘Pediatric ED’ with ongoing monitoring.”

Strategic Analysis

- Objective Description of Distress: The narrative uses specific, objective terms like “subcostal and intercostal retractions” and “3-4 word sentences” instead of vague descriptors like “trouble breathing.” This provides a clear clinical picture.

- Pediatric-Specific Data: It explicitly includes the patient’s weight (20 kg), which is critical for verifying medication dosages and for the receiving facility. It also notes age-appropriate distress indicators like anxiety and speech pattern.

- Clear Response to Treatment: The report documents both positive changes (improved SpO2, fewer retractions) and persistent signs of distress (tachycardia, tachypnea). This balanced assessment is vital for the receiving clinician to understand the patient’s current status.

Actionable Takeaways

- Document Work of Breathing: Be specific. Note the presence and location of retractions (subcostal, intercostal, supraclavicular), nasal flaring, or head bobbing. This quantifies the severity of distress.

- State the Weight: Always document the child’s weight, whether obtained from a parent, a previous record, or an age-based estimate. This is a non-negotiable step for pediatric medication safety.

- Use Pre- and Post-Treatment Vitals: Documenting vital signs, especially SpO2 and respiratory rate, before and after each intervention (e.g., a nebulizer) provides concrete evidence of treatment efficacy or failure.

5. Sepsis/Infection Alert Documentation

Documenting a potential sepsis case requires a high degree of precision, as early recognition and intervention are directly linked to patient survival. A well-crafted narrative for sepsis highlights key clinical indicators and time-sensitive treatments, ensuring the receiving facility understands the urgency. This documentation is crucial for meeting quality measures established by groups like the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and CMS.

The narrative must clearly communicate the suspicion of sepsis, the evidence supporting it (like SIRS criteria or qSOFA score), and the initial steps of resuscitation. It serves as a critical handoff tool, allowing the hospital team to seamlessly continue the time-sensitive care bundle initiated in the prehospital setting.

Example Narrative: Suspected Urosepsis

“Unit 22 dispatched for an 84-year-old female with altered mental status and fever. Caregiver reports patient has a known UTI and has been lethargic for 12 hours. Patient is febrile at 102.1°F, tachycardic at 122 bpm, tachypneic at 28 breaths/min, and hypotensive at 88/50 mmHg. Patient is responsive to painful stimuli only (GCS 10). Per protocol, a sepsis alert was initiated. IV access established with an 18g AC, and a 500 mL bolus of normal saline was initiated. Point-of-care lactate was 4.2 mmol/L. Receiving hospital, ‘General Hospital ER’, notified of sepsis alert with a 10-minute ETA. Continuous monitoring en route shows persistent hypotension.”

Strategic Analysis

- Systematic Criteria: The narrative explicitly lists the clinical data supporting a sepsis diagnosis (fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension), which aligns with Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria. This provides objective justification for the sepsis alert.

- Time-Sensitive Actions: It clearly documents critical interventions like establishing IV access, initiating a fluid bolus, and obtaining a lactate level. These actions directly address the initial steps of sepsis management.

- Clear Communication: The report specifies that a “sepsis alert” was activated and the receiving facility was notified. This demonstrates proper protocol adherence and ensures the hospital team is prepared for immediate action upon arrival.

Actionable Takeaways

- Document Key Markers: Always record temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. Note any signs of organ dysfunction, such as altered mental status.

- Record Resuscitation Efforts: Specify the volume and type of IV fluid administered. If a lactate level is obtained, document the value and the time of the draw.

- State the Alert: Clearly write “Sepsis Alert Initiated” in your narrative. This phrase is a powerful trigger for the receiving hospital and a key component of many patient care report narrative examples focused on critical care.

6. Psychiatric/Behavioral Emergency Documentation

Documenting a psychiatric or behavioral emergency requires a nuanced and objective approach. The patient care report narrative must clearly articulate the patient’s mental state, potential risks to self or others, and the rationale behind treatment and transport decisions. These reports are critical for ensuring patient safety, facilitating appropriate care at the receiving facility, and providing legal justification for actions such as involuntary holds.

This narrative acts as a crucial communication tool between prehospital providers and mental health professionals. Guidelines from organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) emphasize the need for compassionate yet thorough documentation that captures the full context of the crisis.

Example Narrative: Suicidal Ideation

“Unit 24 dispatched for a welfare check on a 34-year-old female. Upon arrival, found patient tearful and withdrawn in her bedroom. Patient admits to active suicidal ideation with a specific plan to overdose on her prescribed sertraline. States she has a full 30-day supply available. Reports feeling ‘hopeless’ following a recent job loss. Denies homicidal ideation or auditory/visual hallucinations. Patient is oriented to person, place, and time but exhibits a flat affect. History of major depressive disorder and one prior suicide attempt via overdose two years ago. Police are on scene and have initiated an involuntary hold. Patient verbally consents to transport for evaluation. Transported without incident, seated on the gurney without restraints.”

Strategic Analysis

- Risk Assessment Specificity: The narrative explicitly documents key risk factors: an active plan (“overdose on her prescribed sertraline”), available means (“full 30-day supply”), and a significant stressor (“recent job loss”). This provides a clear picture of the imminent danger.

- Objective Behavioral Observations: Instead of subjective labels like “sad,” the report uses objective terms like “tearful,” “withdrawn,” and “flat affect.” This professional language is crucial for clinical documentation.

- Justification for Action: The narrative clearly states the legal basis for transport (“Police are on scene and have initiated an involuntary hold”), linking the assessment findings directly to the intervention.

Actionable Takeaways

- Ask Direct Questions: Document direct quotes or paraphrased answers to crucial questions like, “Do you have a plan to harm yourself?” and “Do you have access to the means?” This specificity is vital.

- Document Pertinent Negatives: Stating what was not found is as important as what was. Mentioning “denies homicidal ideation or auditory/visual hallucinations” helps rule out other immediate threats and conditions.

- Use a Structured Approach: A systematic mental status exam provides a solid framework for your report. You can learn more about structured documentation with this free SOAP note template.

7. Obstetric/Maternal Emergency Documentation

Documenting an obstetric emergency requires a specialized approach, as it involves the care of two patients: the mother and the fetus. These patient care report narrative examples must capture a rapidly evolving situation with precision, ensuring a seamless handover to a facility equipped for high-risk maternal and neonatal care. The narrative must detail assessments and interventions for both patients simultaneously.

Guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stress the importance of documenting key obstetric data like gestational age, fetal heart tones, and contraction patterns. This information is critical for the receiving obstetrics team to anticipate needs and mobilize resources, such as the NICU or surgical staff, before the patient even arrives.

Example Narrative: Preeclampsia with Severe Features

“Unit dispatched to a 28-year-old female, G1P0 at 34 weeks gestation, complaining of a severe headache and visual disturbances (‘seeing spots’). Patient is alert but anxious. States symptoms began one hour ago and are worsening. Initial vitals: BP 188/112, HR 98, RR 20, SpO2 99% on room air. Physical exam reveals +2 pedal edema. Patient denies contractions or vaginal bleeding. Fetal heart tones auscultated at 150 bpm. Placed patient in left lateral recumbent position and initiated transport to ‘University Hospital’ OB unit. IV of Lactated Ringers established TKO. Transport was uneventful, continuous monitoring maintained. Report given to receiving OB nurse upon arrival.”

Strategic Analysis

- Dual-Patient Focus: The narrative distinctly documents key findings for both the mother (severe hypertension, headache, edema) and the fetus (gestational age, heart tones). This dual assessment is non-negotiable in obstetric emergencies.

- Specific Obstetric Terminology: The use of “G1P0” (gravida 1, para 0) and “34 weeks gestation” immediately communicates the patient’s obstetric history and viability, which guides treatment and transport decisions.

- Justification of Interventions: Placing the patient in the left lateral position is a specific intervention to prevent aortocaval compression. Documenting this action demonstrates clinical understanding and proper management.

Actionable Takeaways

- State Gestational Age First: Always document the estimated gestational age (in weeks) and gravidity/parity (G/P) at the beginning of your report. This single piece of data frames the entire clinical picture.

- Quantify Bleeding: If bleeding is present, avoid subjective terms like “heavy.” Instead, document the number of saturated pads over a specific time period (e.g., “saturated two pads in 30 minutes”).

- Document Pertinent Negatives: Note the absence of key symptoms. In the example, stating the patient “denies contractions or vaginal bleeding” helps rule out other immediate threats like preterm labor or placental abruption.

8. Allergic Reaction/Anaphylaxis Documentation

Documenting an allergic reaction, especially life-threatening anaphylaxis, requires a narrative that captures rapid assessment and immediate, decisive action. The patient care report for these cases is a critical tool for communicating the severity of the reaction, the specific interventions administered, and the patient’s response. A well-written narrative guides ongoing hospital care and highlights the need for continued monitoring for potential biphasic reactions.

This report must clearly detail the timeline from exposure to symptom onset and treatment. As emphasized by organizations like the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI), the narrative must justify the administration of epinephrine and track the patient’s physiological changes, painting a complete clinical picture for the receiving facility.

Example Narrative: Peanut-Induced Anaphylaxis

“Unit 25 dispatched to a 24-year-old female with an acute allergic reaction. On arrival, patient is in respiratory distress, speaking in 1-2 word sentences. Patient’s friend states she ingested a cookie approximately 10 minutes prior, later realizing it contained peanuts (known allergy). Patient presents with diffuse urticaria, periorbital angioedema, and audible wheezing. Initial vitals: BP 90/60, HR 128, RR 28, SpO2 89% on room air. Epinephrine 0.5 mg IM administered to the lateral thigh. Oxygen applied at 15 LPM via NRB. Following epinephrine, patient’s wheezing improved, RR decreased to 20, and SpO2 increased to 95%. IV established with 500 mL Normal Saline bolus initiated. Diphenhydramine 50 mg IV and Methylprednisolone 125 mg IV administered. Patient transported emergent with continuous cardiac and SpO2 monitoring.”

Strategic Analysis

- Trigger and Timeline: The narrative clearly identifies the suspected trigger (“peanuts”) and establishes a critical timeline (“10 minutes prior”). This context is crucial for understanding the reaction’s severity.

- System-Based Assessment: The report documents effects on multiple body systems: integumentary (urticaria, angioedema), respiratory (distress, wheezing), and cardiovascular (hypotension, tachycardia). This systematic approach confirms a multi-systemic anaphylactic reaction.

- Intervention and Response: The primary intervention (epinephrine) is documented first, along with its specific dose, route, and the patient’s positive response. This demonstrates adherence to gold-standard anaphylaxis protocols.

Actionable Takeaways

- Document Key Times: Note the time of exposure, symptom onset, and each medication administration. These markers are vital for clinical decision-making and quality review.

- Be Specific with Symptoms: Instead of “trouble breathing,” use descriptive terms like “audible wheezing,” “stridor,” or “speaking in single words.” This provides a more accurate depiction of airway compromise.

- Prioritize Epinephrine: Your narrative should reflect that epinephrine is the first-line treatment. Clearly state it was given immediately upon identifying signs of anaphylaxis, followed by secondary treatments like antihistamines and steroids.

8-Case Patient Care Narrative Comparison

| Topic | Implementation Complexity 🔄 | Resource Requirements ⚡ | Expected Outcomes 📊 | Ideal Use Cases ⭐ | Key Advantages / Tips 💡 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest Pain / ACS Documentation | High — detailed EKG/troponin interpretation, timeline documentation | High — EKG, cardiac enzymes, meds (ASA, NTG, heparin), trained EMS/ED staff, rapid transport to PCI center | Timely identification of STEMI/NSTEMI; supports rapid reperfusion and quality metrics | Suspected MI, chest pain with ischemic changes, prehospital STEMI alerts | Standardize EKG reporting; document times (door‑to‑balloon); use objective findings |

| Stroke Alert / Neurological Emergency | High — time-critical neuro scales (NIHSS/Cincinnati), precise timing | High — neurologic assessment tools, CT/MRI access, stroke center capability | Faster tPA/thrombectomy decisions; improved functional outcomes if within window | Acute focal deficits, LKN within treatment window, suspected large‑vessel occlusion | Record exact LKN time; use standardized scales; check glucose immediately |

| Trauma / Motor Vehicle Accident Documentation | High — multi‑system assessment, mechanism detail, scoring (GCS, RTS) | Very high — extrication resources, trauma team, imaging, blood products | Appropriate triage to trauma center; improved survival for major trauma | High‑energy MOI, ejection, multiple injuries, hemodynamic instability | Describe mechanism precisely; document GCS, interventions, extrication and transfer details |

| Pediatric Respiratory Distress / Asthma | Moderate to high — age/weight dosing, pediatric assessment tools | Moderate — weight scale/estimate, nebulizers, PALS‑trained staff, oxygen | Rapid recognition and treatment; reduce dosing errors and deterioration | Acute asthma exacerbation, bronchiolitis, anaphylaxis in children | Always record weight; use age‑appropriate vitals and severity scores; document response |

| Sepsis / Infection Alert | Moderate to high — multi‑organ assessment and timed bundle elements | High — lactate, blood cultures, rapid antibiotics, IV fluids, monitoring | Improved survival with early antibiotics and resuscitation; measurable protocol adherence | Suspected infection with hypotension, altered mentation, organ dysfunction | Time antibiotics and lactate; document cultures and fluid volumes; note reassessments |

| Psychiatric / Behavioral Emergency | Moderate — detailed safety assessment, legal/ethical documentation | Low to moderate — trained clinicians, restraint/chemical sedation options, psychiatric placement | Improved safety, legal protection, appropriate psychiatric disposition | Suicidal/homicidal ideation, acute psychosis, severe agitation | Ask direct SI/HI questions; document intent, access to means, prior history |

| Obstetric / Maternal Emergency | High — dual‑patient focus, gestational specifics, fetal monitoring | High — fetal monitoring, OB capabilities, hemorrhage control, blood products | Maternal and fetal stabilization; timely transfer to obstetric center | Preeclampsia/eclampsia, hemorrhage, emergency delivery, abnormal fetal tones | Establish gestational age; quantify bleeding; document fetal heart tones and contractions |

| Allergic Reaction / Anaphylaxis | Low to moderate — clear protocol but rapid recognition required | Moderate — IM epinephrine, airway support, observation, adjunct meds | Rapid reversal of anaphylaxis; prevention of biphasic reactions with monitoring | Rapid onset allergic reactions with airway or cardiovascular involvement | Give IM epinephrine immediately; document time, dose, route and response; observe for 4–6 hrs |

Automating Accuracy: The Future of Patient Narratives

Mastering the art of the patient care report is an essential, ongoing process. Throughout this article, we’ve explored a range of patient care report narrative examples, from acute coronary syndrome to pediatric emergencies, breaking down what makes them effective. Each example underscores a set of core principles that separate a merely adequate report from an exceptional one.

The most critical takeaway is that a strong narrative is built on a foundation of objectivity, chronological clarity, and comprehensive detail. Whether documenting a trauma activation or a behavioral crisis, the goal remains the same: to paint a vivid, factual picture of the patient’s condition and the care provided. This creates a seamless, legally sound record that supports continuity of care, quality assurance, and billing.

Key Principles for Effective Narratives

Reviewing the diverse scenarios, several universal best practices emerge:

- Tell a Chronological Story: Always start from the beginning. Document the dispatch information, your arrival on the scene, initial patient contact, assessment, interventions, and transport in a logical sequence. This structure makes the report easy for anyone to follow.

- Be Objective and Specific: Replace vague terms with concrete data. Instead of “the patient was breathing fast,” write “patient exhibited a respiratory rate of 32 breaths per minute with audible wheezing.” Quantifiable metrics and direct observations are your strongest tools.

- Document Pertinent Negatives: What you didn’t find can be just as important as what you did. Documenting the absence of JVD in a cardiac patient or the lack of head trauma in a fall victim helps rule out other conditions and demonstrates a thorough assessment.

- Justify Your Actions: Your narrative should clearly explain the “why” behind your interventions. Connect each treatment directly to a specific assessment finding, such as “administered nitroglycerin for the patient’s reported 8/10 substernal chest pain.”

From Manual Effort to Automated Excellence

While these principles are timeless, the methods for achieving them are rapidly evolving. The administrative burden of manual documentation is a significant challenge, consuming valuable time that could be spent on patient care. This is where technology offers a transformative advantage. To delve deeper into the specifics of healthcare documentation, exploring specialized medical transcription guides can offer valuable insights into existing practices and the immense potential for automation.

Modern platforms are revolutionizing this entire process. For instance, AI-driven tools can now capture patient histories and clinical interactions through voice, then automatically translate that conversation into structured EMR data. This approach not only slashes documentation time but also significantly enhances accuracy and consistency. By embracing these advancements, healthcare organizations can empower their clinical staff to focus exclusively on what they do best: providing exceptional, hands-on patient care.

Ready to eliminate administrative burdens and perfect your patient narratives? Discover how Simbie AI uses advanced, clinically-trained voice AI to automate documentation, reduce errors, and free your team to focus on patients. Learn more about Simbie AI and see the future of patient care reporting today.